To the outsider, Tordesillas looks like just another small town on the banks of the River Douro in the Spanish province of Valladolid.

It has a historic center with a typical plaza mayor (central square) and churches dating back to the Middle Ages. But mention the name of the city in any city in South America and many people will immediately make the connection: it was there, in 1494, that Spain (then known as the Kingdom of Castile) and Portugal signed a commitment to divide the territories they discovered – the Treaty of Tordesillas.

A decision that played a crucial role in making Brazil the only Latin American country with Portuguese as its language.

The city’s location made it the perfect place for negotiations between the two kingdoms. “Tordesillas was at the crossroads of very important roads at the time,” explains Miguel Angel Zalama, director of the Tordesillas Center for Ibero-American Relations.

“There was also a palace and everything indicates that the treaty was signed there.”

The place is now known as Casas del Tratado, and there’s nothing very luxurious about it. But it does house a museum and a replica of the historic document – this is because the original in the possession of the Spanish is at the headquarters of the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, which houses all the documentation from the Spanish colonial period.

The presence of a comfortable location and ease of access may not have been the only reasons why the Spanish monarchs, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, chose Tordesillas.

“In the 14th century, Queen Maria of Portugal and her daughter Beatriz lived there, so the city had a historical connection with the country. It’s possible that Castile made a political gesture to make the Portuguese feel more comfortable,” explains Ricardo Piqueras Céspedes, a historian at the University of Barcelona.

Isabella and Ferdinand had good reason to appease Portugal. The process of negotiating the Treaty of Tordesillas had lasted a year and was marked by uncertainty, as well as the threat of war between the two countries, pioneers of the Great European Navigations.

The negotiations began when, on his return from his first voyage to the Americas, the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus, who was in the service of Castile and Aragon, was forced to stop in Lisbon to avoid a storm. He was forced to give a travel report to the Portuguese king, João 2º. The monarch, convinced that the new lands were covered by the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo, which gave Portugal ownership of discoveries south of the Canary Islands, claimed ownership of what Columbus had found.

However, the captain of another ship taking part in Columbus’ expedition, the Pinta, managed to reach Castile and immediately sent news of the discovery to the monarchs. They sent emissaries to Pope Alexander 6th to claim it.

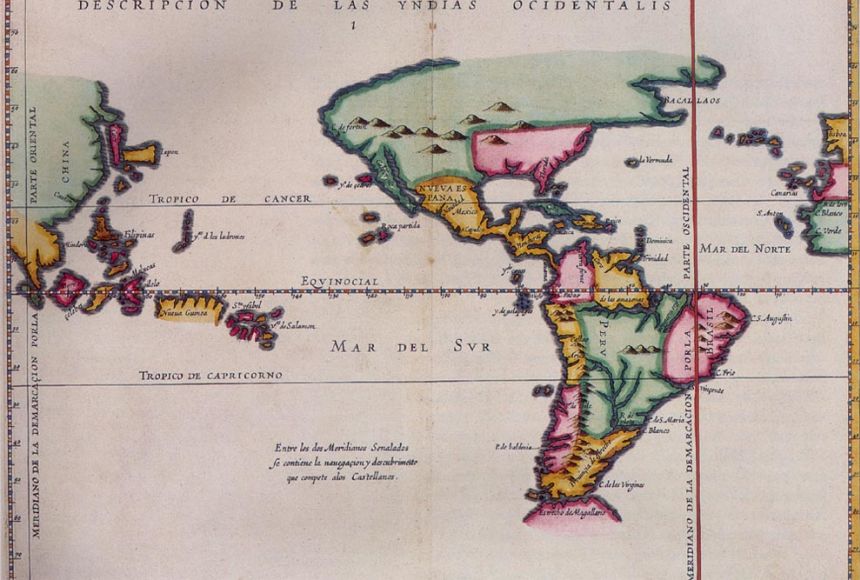

The pontiff then issued three Papal Bulls. The first of these, on May 4, 1493, entitled Bula Inter Caetera, basically canceled the Treaty of Alcaçovas-Toledo, creating a vertical, pole-to-pole demarcation of the Atlantic instead of a horizontal one.

The new terms were disadvantageous for Portugal, which in addition to losing the new lands found itself “cornered” in its expansion into Africa, since the imaginary line drawn by the pope’s order passed just 420 kilometers west of the island of Cape Verde.

“The Portuguese wanted to preserve their African colonies and islands in the Atlantic, but to sail to them they needed favorable winds. And that would force the navigators to make long turns. But the line determined by the bull prevented the Portuguese from sailing without invading Castilian territory,” says Zalama.

Intense diplomatic activity tried to prevent the countries from going to war and at the same time negotiate a solution.

In the midst of the discussions, in September 1493, Columbus set off on his second voyage, promising to pass on information to the Spanish monarchs that would help the negotiations. In April 1494, he sent them a map of his discoveries. Not knowing whether John II had agreed to give up the horizontal division, he tampered with the map, “raising” the altitude of Hispaniola – the island that is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, found during his first voyage. He placed it several degrees to the north, on the same parallel as the Canaries, so that this would result in Spanish domination under the terms of the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo.

But when the map arrived, Portugal had already accepted the vertical partition. More concerned about the passage to Africa, João 2º only asked that the imaginary line be moved to more than 1,500 km from Cape Verde. This would guarantee Portugal the lands to the east of the line, with the west remaining with Spain.

As Columbus’ map showed no territories on the Portuguese side, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to the Portuguese monarch’s demand.

None of them knew it, but the new line crossed part of what is now northeastern Brazil. In 1500, with the arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral, Portugal incorporated Brazil into its possessions and, over the course of two centuries, expanded its territorial presence in the region – which ended up being the only part of the continent where Portuguese is spoken.

Incredibly, the signing of one of the most important treaties in history didn’t turn Tordesilhas into a famous destination.

The town has less than 10,000 inhabitants and is often in the news more because of the protests by animal rights groups against the Toro de la Vega, an annual festival in which a bull is chased through the streets by hundreds of people. Until 2016, the animal was killed, but the practice was banned by the regional government.

The history of Tordesillas is not only linked to the treaty. Founded in 1262, it was an important bastion during the Reconquista – the process of retaking the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim forces.

The city also has a sad reputation: its most famous building, the Convent of Santa Clara, was for almost 50 years a prison for Joan 1st, daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand, who ascended the throne upon her mother’s death in 1504. On her father’s orders, and on the grounds that she was insane, she was locked up in 1509 and remained there until she died in 1555, even after her son, Charles 1st, took the throne in 1519.